“The saying I’ve always heard is ‘bloom where you are planted.’ If it is in Iowa,… There is a lot of room here for Black people’s accomplishments… it doesn’t mean you can do it overnight. You have to stick with the stuff until you achieve the goal that you set in the first place…”

– Bernice Jones, Narratives of African Americans in Iowa (Charline J. Barnes), 2001, p. 124

It All Started With a Swimming Pool

Viola Gibson was a towering figure in Cedar Rapids from the 1940 until her death in 1989.

In 1941, Gibson was upset to find out that her nephew was not allowed to enter the new Cedar Rapids swimming pool at Ellis Park. Blacks and whites had previously shared the beach at Ellis park without any problems. She joined others in reactivating the Cedar Rapids branch of the NAACP.

Viola Gibson liked to collect china. These pieces were purchased at the estate sale following her death.

Click on the hotspot to see the collections record for the pitcher in our online database.

Putting African Americans to Work in Good Jobs

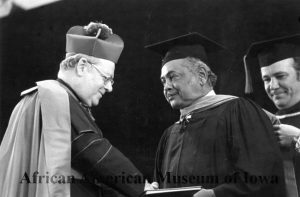

Charles Toney began working at John Deere in 1936 where he soon became the first African American welder. In 1964 he moved to John Deere’s corporate office, becoming a Personnel Representative. He began recruiting African American college students from historically African American colleges and eventually built a massive network between John Deere and these colleges.

In 1972 he became the first African American senior executive at John Deere when he was named Director, Affirmative Action. He developed and instituted many programs target at bringing more African Americans into John Deere during his tenure.

Honorary Degree from St. Ambrose College, 1975

Charles Toney received many awards for all of his work promoting Civil Rights and affirmative action. In 1975, he was the first African American to receive an honorary degree from St. Ambrose College in Davenport.

Black and white photograph of African American Civil Rights activist Charles Toney receiving his honorary degree from St. Ambrose.

The Journey

by Heather Wagner, Cedar Rapids

This mural portrays the journey African Americans made from their roots in Africa to present-day Iowa. The Midwest’s rolling hills and open sky are the backdrop. The journey begins in the bottom and the timeline crawls from the depth of slavery up the hills and through valleys until the tops of those hills are in sight, conquered and leaving the sky an open canvas, representing the future of Iowa’s African Americans.

“The worst thing that colonialism did was to cloud our view of our past.”

― Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance

Engungun figure

The Yoruba of Nigeria believe that ancestors take interest in the world of the living and are a moral force with the ability to punish or bless their descendants. Masqueraders move between the worlds of the dead and the living and oversee the moral order of society.

This mask, with its large size and rich attire, represents the spirit of an Egungun erin, or elephant ancestor. The Yoruba believe this ancestor can bring money, children, and other blessings to those who offer it sacrifices. The performer wearing this mask moves slowly, dancing and singing songs of blessing.

Egungun mask, Yoruba people in Nigeria, mid 1900s

Courtesy of Dr. Norma Wolff

Masks

Masks in Africa have a variety of purposes, including invoking the spirits of nature, ensuring the well being of a community, and entertaining. Masks are part of agricultural celebrations, funerals, adulthood initiations, and village purification rites. These masks are all from Burkina Faso. They are made of ceiba wood, and decorated in geometric designs of red, white, and black.

Bwa Helmet Mask – The antelope symbolizes the power of the forest. Its horns are used in magic and as charms. The Bwa people wear antelope masks during annual ceremonies and funerals to protect humans from evil spirits.

Beginnings

Africa, the world’s second largest continent, is over three times the size of the United States and is home to a rich variety of cultures. Great civilizations have thrived throughout Africa’s long history. Several nations in West Africa flourished during the period of European contact by facilitating trade of all kinds between the seafarers and people in the interior.

Africa contains 54 countries. The climate and the landscape of the continent vary widely from north to south and from east to west. There are vast contrasts in the landscape of the continent ranging from deserts in the north and south to rainforests in the center of the continent.

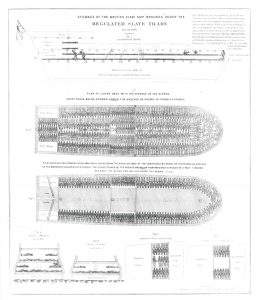

“The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, being so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died…”

– Bernice Jones, Narratives of African Americans in Iowa (Charline J. Barnes), 2001, p. 124

The Door of No Return

This portion of our exhibit is based on the doors of the slave fort on Goree Island off the African coast. Places such as this remain a testament to the slave trade.

Europeans build forts to use as trading posts and holding pens. The fort on Goree Island, built by the dutch in 1617, was constructed of bricks brought from Europe as ship ballast. The island and fort were occupied at various times by Portuguese, French, and English until 1763.

Door under construction at Split Rock Studios

Importing & Selling Slaves

In 1619 a Dutch ship unloaded the first African captives to arrive in the English colonies that would later become the United States at Jamestown, Virginia. At that time, African captives and many white Europeans served as indentured servants, freed after working for several years. Over time, indentured servitude became less common while it became more common for African captives to be denied freedom.

The Atlantic slave trade was the largest forced migration in human history. By the 1860s, at least 35,000 slave ship voyages traveled across the Atlantic on a voyage known as the Middle Passage and delivered over 10 million living Africans to the Western Hemisphere. Slave importation peaked during 1700 and 1770, with over 250,000 slaves brought to the United States alone during that period. The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves took effect in 1808, but many European nations participated in illegal slave trade with the United States until 1860. By the 1860s, at least 35,000 slave ship voyages had crossed the Middle Passage.

Deadly Conditions

An estimated 30% of enslaved Africans died during the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean aboard slave ships. Many others never even made it aboard ship and died while being transported to the African coast or waiting for ships to arrive at slave forts.

Plan of the British Slave Ship Brookes, 1789 – Library of Congress

This British slave ship was permitted to carry 454 slaves, as shown in this plan. Prior to the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, the ship carried between 609 and 740 slaves. The horrible conditions aboard slave ships resulted in millions of deaths. The length of the voyage varied greatly, typically ranging from one to six months, depending on conditions, weather, origin, and destination.

Human Cargo

The Atlantic slave trade launched the largest forced migration in human history. Slave ships crossed the Atlantic Ocean via the infamous Middle Passage, delivering 9 to 12 million living Africans between 1510 and the mid-1850s.

An estimated 30 percent of enslaved Africans died during these voyages. In addition, many others died while being transported to the African coast and while waiting for ships to arrive.

Portugal dominated the slave trade beginning about 1450, and France, Denmark, Holland, Spain, and Great Britain eventually wanted part of this lucrative business.

Click on this hotspot to see a Google Maps 360 view of this section of the exhibit.

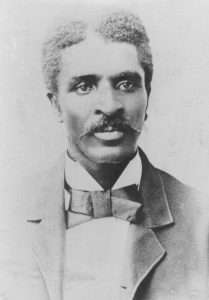

“When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.”

– George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver was born a slave in Missouri during the Civil War and was raised by his mother’s former owners. He left home at an early age to seek education.

In 1881 he became the first African American student at Iowa State University. After graduating from Iowa State, Carver became a well-known scientist at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama developing new industrial uses for the soybean, pecan, sweet potato and the peanut and specializing in a field known at the time as “Chemergy,” but known today as bio-chemical engineering. Carver died in 1943.

Making a Living

Before the Civil War, African Americans migrated to Iowa and found employment as servants or laborers, and many settled in Mississippi River towns. From 1880 to 1920, common occupations for African Americans included coal miner, railroad worker, and manual laborers.

African Americans have operated small businesses in Iowa since the 1830s. Small numbers of African American professionals began to appear in Iowa after the Civil War.

Miles Dawson with Sons

African Americans have farmed in Iowa since it became a territory in the 1830s. In the 1850s, a number of African Americans from Illinois settled in Fayette County and formed a farming colony. After the Civil War, the number of African American farmers increased reaching 325 by 1900. For example, the Dawson family first moved to Iowa around 1900, settling in Lee County in southeast Iowa. Seven of Miles Dawson’s eight sons became farmers, and his daughters married farmers. By the 1920s, Dawsons had settled on farms throughout the southeast Iowa region.

Miles Dawson and his eight sons, circa 1925 | Collection of AAMI – Gift of Donna Harris

Churches

African Americans expanded Christianity in their own way, creating a whole new theology and style of worship. Slaves brought their religions from Africa but were also converted to Christianity by slave owners. In the South, some slaves worshiped separately, but others were forced to attend church with their masters.

In the North, for a time, African Americans attended churches with whites, but racism and a desire for their own churches led to the founding of the African Episcopal Church and the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.) in 1794.

Bethel A.M.E Church |

Oscar Grossheim Collection of the Musser Public Library

In Iowa, the formation of African American churches began in the 1840s and 1850s. Most of these early churches were A.M.E.

Click on this hotspot to see a Google Maps 360 view of this section of the exhibit.

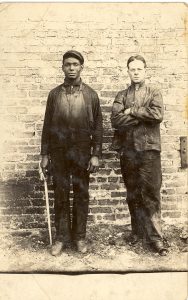

Buxton Miners

From the 1880 – 1920 coal mining, the second largest industry in Iowa, was the most common occupation for African Americans. The largest number of African American miners in Iowa were located in the majority African American coal camps of Muchakinock and Buxton.

Buxton miners, circa 1910 | Courtesy of the Monroe County Historical Society

We, the undersigned residents of Iowa, call upon you to enforce state civil rights laws which guarantee ALL persons the “full and equal enjoyment” of being served at lunch counters….We believe that such failure to comply with the law if a challenge to the Iowa tradition of fair play and endangers the rights of all people regardless of race, creed, color, religion or political belief.

– Petition Against Katz Drug Store

Katz Drug Store

The Katz Drug Store chain was founded by Isaac and Micheal Katz in Kansas City, Missouri. Click on the hotspot to see a photos from the Des Moines Register of the Des Moines location and Edna Griffin’s protest.

“We Shall Not Be Moved”

Edna Griffin led a series of sit-ins in 1948 and 1949 at the Katz Drugstore that was located adjacent to an African American neighborhood in Des Moines. She and others also circulated petitions throughout Iowa, asking the governor to enforce Iowa’s Civil Rights law.

The Katz Drugstore was targeted because the owner refused to serve blacks, even though he was repeatedly convicted of this violation. The courageous protests of 1948-1949 finally forced him to change his discriminatory policy and serve African Americans at his Des Moines store.

Counter installation in progress, 2009

Click on this hot spot to see a Google Maps 360 view of this section of the exhibit.

If you enjoyed this digital exhibit tour, consider making a donation or becoming a member to enable us to continue to create online opportunities for people around the world to engage with Iowa’s African American history.