In light of the June 17, 2020 news that the Aunt Jemima brand will change it’s name and image, we are sharing this article from the Summer 2016 issue of the Iowa Griot. This article was written by Brianna Kim, who was the AAMI curator at the time of publication and now holds the position of Operations Director.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, it was not uncommon to see stereotypical depictions of African Americans in mainstream entertainment and advertising directed at white consumers. Along with the pickaninny, Uncle Tom, Sambo, and Jezebel was the Mammy. She was usually depicted as an older, large, matronly black slave or servant who spent her life happily cooking and cleaning. In the antebellum period, Mammy was used as “proof” that slaves were happy; in the Jim Crow era, a time when black women had few employment opportunities outside domestic service, she was used to justify their oppression. One of the best-known and most successful uses of the Mammy archetype in advertising was Aunt Jemima.

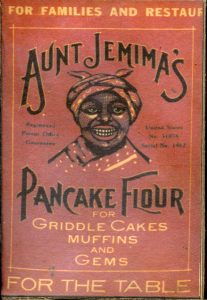

Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour box, early 20th century

Collection of AAMI – Gift of Harvey W. Dewey

Introduced in 1889, Aunt Jemima pancake mix was the first ready-made food product sold commercially in the United States. The brand was founded by Chris Rutt and Charles Underwood of St. Joseph, Missouri. As the story goes, the product’s name was inspired by a character in a minstrel show that Rutt attended. The white man in blackface wore women’s clothes and performed the song “Old Aunt Jemima.”

When the Aunt Jemima brand was sold to R.T. Davis in 1890, he not only improved the product but decided to make Jemima a “real” person and hired Nancy Green, a former slave, to portray her. She made her debut at the 1893 World’s Fair. Quaker Oats purchased the company in 1926 and trademarked Aunt Jemima in 1937. Several other women – including Anna Robinson, Edith Wilson, Rosie Hall, Ethel Ernestine Harper, and Aylene Lewis – portrayed Aunt Jemima until the 1960s. Advertisements, targeted primarily at white women, developed a back story for the character and her secret pancake recipe. As M.M. Manring states in the book Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima, “The ads urged white housewives to have Aunt Jemima, not to be Aunt Jemima.”

Aunt Jemima and Uncle Mose salt and pepper shakes

Collection of AAMI – Gift of Harvey W. Dewey

In the early to mid-20th century, the success of the Aunt Jemima brand had extended into several premiums and promotional products. The line included a set of dolls, spice shakers, and cookie jars featuring Aunt Jemima, her husband Uncle Mose, and their children.

The onset of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements of the 1960s and 1970s sparked renewed resistance to stereotypical advertisements. “Aunt Jemima” had become an insult in the African American community, referring to a person whose actions and mindset hindered progress towards true equality.

In 1968, Aunt Jemima’s image underwent significant changes. She became slimmer and younger. Her bandanna, to many a symbol of slavery and servility, was replaced with a headband. The current image used on Aunt Jemima packaging, a smiling women with curly hair and pearl earrings, dates to 1989.

Sources

Fuller, Lorraine. “Are We Seeing Things?: The Pinesol Lady and the Ghost of Aunt Jemima.” Journal of Black Studies 32.1 (2001): 120-31.

Manring, M. M. Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. Charlottesville: U of Virginia, 1998. Print.

Pilgrim, David. ” The Mammy Caricature.” Jim Crow Museum: The Mammy Caricature. Ferris University, 2012.

These items from the AAMI collection were donated by Harvey W. Dewey. In these images, you can see how stereotypical depictions of African Americans were used in the Aunt Jemima branding. These images also show how these caricatures were prevalent not only in the product packaging, but extended into household goods such as paperweights and clocks. As you look at these items, think about how it might have felt to be a young black person growing up surrounded by images like these as popular depictions of your race.

This video from the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University shows additional examples of how the Aunt Jemima brand has been marketed over the years, including audio clips from commercials.

![Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour Box Small rectangular box of Aunt Jemima pancake flour. Box has the text: [AUNT JEMIMA/ PANCAKE FLOUR / MADE BY/ THE QUAKER OATS COMPANY/ ADDRESS CHICAGO U.S.A.] The front and back of the box has a black and light sepia colored drawing of Aunt Jemima with a plaid type scarf covering her head. The background color of the box is a burnt sienna.](https://blackiowa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/c2009016001-180x180.jpg)

![Aunt Jemima Buckwheat Box Cardboard salesman's sample box of Aunt Jemima Ready-Mix Buckwheat pancakes. Front of box has yellow background with shoulders-up image of "Aunt Jemima" character. She is wearing white clothing and a red and white checked head scarf. Black and red printing superimposed on her clothing reads, [AUNT JEMIMA / READY-MIX / BUCKWHEAT / WHEAT and CORN FLOUR / PREPARED WITH CORN SUGAR, PHOSPHATE, SODA, SALT, RICE FLOUR, AND DEFATTED MILK SOLIDS / WEIGHT 1 LB. 4 OZ. NET / MANUFACTURED BY The Quaker Oats Company ADDRESS CHICAGO U.S.A.].](https://blackiowa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/c2009016004-180x180.jpg)

![Aunt Jemima Clock Metal alarm clock with image of Aunt Jemima character on face. Clock is metal with a glass plate over the face. Glass plate is attached to clock with three screws. Clock is round and is screwed to a base with two screws. Face of clock has numbers 1-12, black hour and minute hands, and smaller white hand above. Hour and minute hands are attached at the nose of an image of Aunt Jemima, an African American woman with a red head scarf. Printing on head scarf reads, [AUNT JEMIMA'S / PANCAKE FLOUR / ASK YOUR GROCER]. Bottom of face has printing reading, [THE LUX CLOCK MFG. CO. INC. LEBANON, TENN., U.S.A.]. Top of clock has two metal switches, each of which is associated with two white rectangles. Faint printing on second rectangle from right reads, [STEADY]; printing is illegible on far right rectangle and gone from two left rectangles. Back of clock has two winding mechanisms, one reading [ALARM] and the other [TIME]. Two other dials have no labels. An arc-shaped hole in the top proper left of the back has an [S] at one end and an [F] at the other. There is a foot at the bottom center to support the clock if it is tipped back. Printing at bottom proper left of back reads, [PATENTED / JUNE 9, 1908 / DEC. 15, 1908 / AUG. 29, 1911 / NOV. 9, 1920 / PATENTS PDG.]. Clock works.](https://blackiowa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/c2009016009-180x180.jpg)

![Aunt Jemima Wood Sign Wooden panel from a shipping crate. Has black stamped image and words. Has a circle with crude woodcut type image of Aunt Jemima character (an African American woman in a head scarf), with the words [TRADEMARK] and [REGISTERED] on the left and right of the image, respectively. Writing reads, [AUNT JEMIMA'S / PAN CAKE FLOUR / KEEP DRY / R.T. DAVIS MILL CO. ST. JOSEPH. MO.]. Both the word [Aunt] and the words [Pan Cake Flour] are on banner backgrounds. There are nail holes on the right and left extreme ends of the panel: four holes per side. There are three nail holes, two with broken nails in them, on the bottom of the panel. There is one nail in the top of the panel; its point comes through the front of the panel just above the word [Aunt].](https://blackiowa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/c2009016011-180x180.jpg)

![Aunt Jemima Needlebook This a needlebook in the shape of an Aunt Jemima's Pancake Flour box. The booklet is opened and placed between glass then encased in a brown wood frame. The right side of the book cover is red and the image of Aunt Jemima is in the center. The patent number on the right side is [51056] and the serial number underneath is [1462]. On the front, the inscription at the top includes the words [THE AUNT JEMIMA NEEDLE BOOK], and below the words [PANCAKE FLOUR/ FOR/ GRIDDLE CAKES/ WAFFLES/ AND MUFFINS/ FOR THE TABLE] On the left side of the cover are pictures of pancakes, waffles and muffins. The back right side has the words [NECESSITY]] at the top and below that is a sheet in which three needles are inserted. Below that is a statement about the economic value and product guarantee. On the left side, a title states [A HOUSEHOLD]. Below are drawings of what appears to be Aunt Jemima's family. Over their heads are the words [ISE IN TOWN HONEY]. Information follows about ingredients, how to acquire recipes, and cloth rag dolls in color that represent Aunt Jemima's family. The pictures of the family are a stylize stereotypical depiction of African Americans.](https://blackiowa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/c2009016012-180x180.jpg)