While we are closed in response to the spread of COVID-19, we want to ensure that our educational resources remain available to the public. Over the next few weeks, we will be sharing information from our exhibits and archives. For our first post during this time, we thought that it would be appropriate to share the stories of a few of the medical pioneers featured in our 2015-2016 exhibit Products of a Creative Mind. All of the text here has been adapted from that exhibit.

If you would like to help ensure that we can continue to offer our educational resources during our closure, consider making a donation or becoming a member of the Museum.

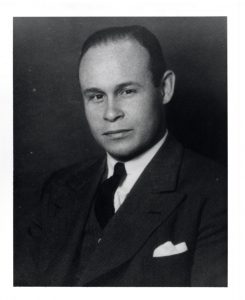

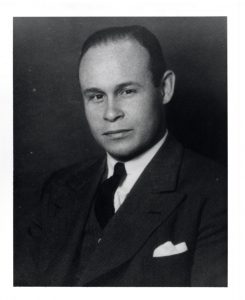

Dr. Percy Lavon Julian – Via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Percy Julian

If you’ve ever received cortisone shot to relieve pain or inflammation, thank Dr. Percy Julian. After receiving a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from DePauw University in 1920 and a master’s from Harvard in 1923, Julian went on to study at the University of Vienna, where he received his doctorate in 1931.

While in Vienna, Julian’s research focused primarily on physostigmine (also called eserine), a compound used to treat glaucoma and Alzheimer’s disease. Though its medical benefits were well-known, no one had yet been able to synthesize the drug. When Julian returned to the United States, he brought with him Josef Pikl, a colleague from Vienna. While working at DePauw in 1935, Julian and Pikl became the first to successfully synthesize physostigmine. By doing so, they made the treatment of glaucoma more affordable and thus, more widely available.

Julian left DePauw in 1936 after funding for his research and salary ran out. He was denied a faculty position due to his race and experienced similar discrimination when received a job offer in Appleton, Wisconsin that was later rescinded when it was discovered that the city had a law forbidding black residence. Julian was eventually hired by the Glidden Company in Chicago to lead its Soya Products division and find uses for soybean oil by products.

Portrait of Charles Drew – Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Charles Drew

During World War II, the lives of countless soldiers and civilians were saved by the pioneering work of Dr. Charles Drew. After working at Morgan State College in Baltimore for two years as director of athletics and an instructor of biology, Drew began medical school at McGill University in Montreal, Canada in 1928. Here he was introduced to research in the field of blood preservation and transfusion. He graduated in 1933 with a doctor of medicine (M.D.) and master of surgery.

After teaching at Howard University’s College of Medicine from 1935-1938, Drew received a fellowship to study at Columbia University, where he completed his doctoral thesis on “Banked Blood.” His work included research on plasma, the liquid portion of blood. Plasma can be used as a substitute for whole blood and stored significantly longer. Drew received a doctor of science (Sc.D.) from Columbia in 1940, the first African American to receive such a degree in the United States.

Later that year, Drew led the Blood for Britain program, established to provide aid to England in the wake of Nazi German air raids. Drew organized the program, coordinated the efforts of several major hospitals, and established procedures to organize donors and collect, store, and ship plasma. When the American Red Cross took over the program in 1941, Drew became its first director. One innovation he implemented was the use of bloodmobiles (mobile blood donation centers). Drew left the Red Cross after several months, possibly due to the organization’s policy that blood donations must be segregated by race.

Drew returned to Howard University in 1941, dedicating the rest of his career to surgery and training black surgeons.

Louis T. Wright and colleagues at patient bedside, Harlem Hospital, New York, N.Y. From left to right: Dr. Lyndon M. Hill, Dr. Louis T. Wright, Dr. Myra Logan, Dr. Aaron Prigot, unidentified African American woman patient, and unidentified hospital employee. – Harvard Medical Library, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, Mass, via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Louis T. Wright

Louis T. Wright had two doctors to look up to – his father, a graduate of Meharry Medical College, and his stepfather, the first African American graduate of Yale Medical School. Following in their footsteps, Wright earned his M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1915.

Entering the Army Medical Corps during World War I brought Wright to Iowa. He completed training at Fort Des Moines, home to the first officer candidate school open to African Americans. While stationed in France, Wright conducted tests that showed intradermal inoculation was more effective than scratch inoculation in vaccinating against smallpox.

In 1919, Wright was hired by Harlem Hospital, becoming the first black staff member at any New York City hospital. Four white doctors resigned in protest. He received several promotions and became director of surgery in 1943. In addition, Wright was the New York Police Department’s first black surgeon.

In 1948, Wright founded the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Foundation, with the goal of advancing studies in chemotherapy, the use of chemicals, to treat cancer. At the time, chemotherapy was a newly emerging concept and one that many physicians did not take seriously.

Jane Cooke Wright – Via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Jane C. Wright

In 1949, Dr. Louis T. Wright’s daughter Jane joined him at the Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Jane C. Wright received her medical degree from New York Medical College in 1945. After completing an internship at Bellevue Hospital and a residency at Harlem Hospital, both in New York, Jane’s intent was to enter private practice. However, when her father asked her to join him, she accepted the offer.

When Dr. Louis T. Wright died in 1952, Jane became the director of the Cancer Research Foundation, where she would conduct pioneering research on the treatment of cancer over the next several decades. Wright tested numerous cancer-fighting drugs on cancerous cells removed from patients and multiplied in a lab. As cancer fighting drugs were introduced, Wright could observe their effects and determine if the drug would be effective on the patient. She was among the first to promote individualized treatments for cancer and the coordinated use of multiple methods (radiation, surgery, and/or chemotherapy) to combat the disease. In addition, her experiments proved that injecting drugs directly onto the location of the cancer was more effective than using a more convenient vein or artery.